at 612-315-3037 or

www.swansonhatch.com

Background on Charities. Fundraising for charitable purposes has existed for over 1,000 years: building amphitheaters in ancient Rome, Buddhist temples in Nepal, and cathedrals in the middle ages. Many charities hire professional fundraisers, which are generally paid out of the proceeds they raise.

A lot of money runs through charities. Americans gave $390 billion to charities in 2016. Over 1.4 million organizations were granted tax exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service. Charitable organizations generate over $1.6 trillion in revenue from services and sales, and their 1.35 million employees comprise about 9.2% of wages paid in this country.

Many Charities Benefit Society. Many, many charities perform generous acts of kindness. Since the 1880s, the Red Cross has aided the military, delivered disaster relief services and has supported blood banks. For more than a century, Goodwill has collected used clothing and household goods and distributed these items to the poor. Almost 200 years ago, the French Ursuline Sisters created an orphanage in New Orleans. Since 1900, over 800 Catholic charities have provided care to children, the elderly, the sick, and the disabled. Since about the same time, Lutheran Services of America has assisted the elderly, children, widows and the disabled. In 1865 a Methodist minister, William Booth, founded the Christian Mission, which—now known as the Salvation Army—has provided basic life necessities and disaster relief to adults, children, and families.

Some Charities Are Also Scams. Unfortunately, some charities have also operated as scams, fleecing the generosity of fellow Americans for the personal benefit of those who run the charity. Fundraising fraud may take the form of using fake names, using names that sound similar to well-known legitimate causes, or misrepresenting programs or the submission of false documents. One of the first sham charities to be prosecuted was the Cripple’s Welfare Society in New York, where George Ryder solicited contributions for his shell corporation and then used the proceeds for his personal gain. In 1989, The Bible Speaks was exposed for tricking elderly donors out of millions of dollars by falsely stating that the donation were being used to free a captive missionary. In 1996, solicitors were stopped from selling “honor boxes” that, when placed next to a merchant’s cash register, would reap profits of $3,000 to $4,000 per month. In turn the merchants paid the solicitors a set monthly fee. According to the Tampa Bay Timesand the Center for Investigative Reporting, 50 charities collectively paid their professional fundraisers nearly $1 billion yet directed less than 10 percent of the money to a charitable mission.

Buyer Beware. The courts have ruled that the government cannot regulate the amount that a charity must spend is on “program expenditures” as opposed to “fundraising costs.” The courts have repeatedly ruled that charities have a First Amendment right to spend some or all their receipts on advocacy and fundraising as long as they do not misrepresent to donors how they spend their receipts. The courts have stated that high fundraising costs are not necessarily connected to fraud and that the government cannot regulate the percentage of funds tied to fundraising or overhead costs. The courts have held, however, that charity cannot misrepresent its programs or the amount of money going to fundraising costs or to program costs.

Compliance Audit of Savers. In 2014, the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office investigated the Minnesota fundraising contracts of the professional fundraiser Apogee Retail, LLC and its parent Company Savers, LLC. (“Savers”). Savers had contracts with Courage Kenny Foundation, Lupus Foundation of Minnesota, the Vietnam Veterans of America, and True Friends. The investigation revealed several problems.

Savers is the largest for-profit thrift retailer in North America, owning 290 retail stores that sell clothing, furniture and household items. Its stores generated more that $762 million in sales in 2010. It had about 15 stores in Minnesota.

The investigation revealed that Savers’ business model involved a subsidiary that operated a professional fundraising company that signed contracts with and raised money for legitimate charitable organizations. The fundraising company would advertise, operate call centers and utilize direct mail to encourage donors to donate used clothing and household goods.

The company also installed donation bins at shopping malls where goods could be donated. The bins are known as “On-Site Donations,” or OSDs. The OSDs were the most profitable for Savers. Savers would then pick up the bags of clothing and furniture at curbside and haul the products to a distribution center, where they were sorted, priced, and placed on the retail thrift chain’s sales floor.

The revenue raised in Saver’s stores was retained by Savers, a for-profit company. Savers then paid the charities based on the volume of goods collected.

The essence of the business model is that the company pays a small fee to the charity and gets to use the charity’s name to solicit donations. Swanson’s audit found that the company commingled donated goods from various charities in the stores without segregating the donated goods by the charity on behalf of whom it purported to collect the goods. In other words, one solicitation campaign might show a disabled child for Courage Minnesota. Another might show a military family for Vietnam Veterans, and another might show a child at a camp site for True Friends. Even though the donor may intend that her donation to go to the advertised charity, Swanson’s audit alleged that goods intended by the donor to benefit one charity were dumped with those intended by another donor to benefit another charity for eventual sale to the public.

Savers Compliance Report. In November of 2014, Swanson issued a 53-page compliance audit report on Savers. The Report stated that Savers paid a specific rate for used clothing, often as little as 40 cents per cubic foot — roughly the equivalent of six dresses. But in turn, Savers would sell the dresses at its retail stores for $6.99 each, keeping about 98 percent of the charitable value.

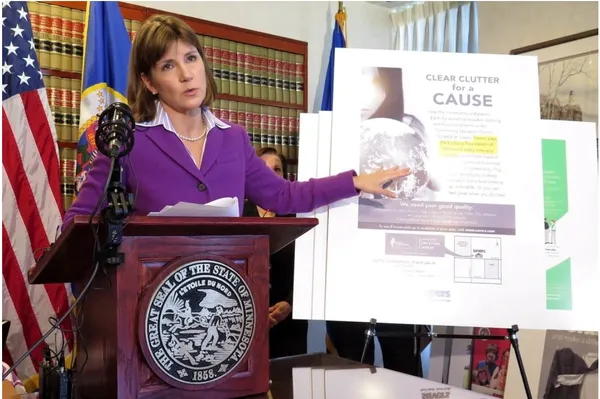

“Here, most of the money is not going to the charity, it’s going to a for-profit outfit. It’s important there be transparency in that relationship,” Swanson said.

One of the biggest surprises in the probe involved donated household furnishings, which were strongly encouraged by Savers. Swanson’s audit found that charities were reimbursed only for clothing under their specific contracts, nor for household goods, or bric-a-bat donations.

“Yet at the same time, they’re handing out tax receipts to people encouraging donors to donate on their taxes, donations of non-clothing items. Essentially writing them off their tax returns as a charitable donation when the charity is not benefitting,” Swanson said.

Savers Lawsuit. In May of 2015, Swanson filed a lawsuit against Savers, pointing out that the donations directed by donors to a particular charity had no relationship to the revenue received by the particular charity. As important, Swanson pointed out that a one-pound suit would sell for $100 in a Savers store and the company may only make a 50-cent donation to the affiliated non-profit. As to household goods, Swanson’s lawsuit said no money was paid to the charities, even though donors were led to believe their donations of household goods would benefit the charities. The company could sell a $200 television set and keep all the money.

Swanson described the business model as a triple scheme: "The donor donates clothing thinking it's going to a community nonprofit at a community neighborhood donation center. But only a sliver ... goes to the nonprofit and the rest is pocketed by the for-profit fundraising company and its executives," Swanson said as she announced the suit. She also said that Savers doesn't give proceeds to the charities it identifies at collection points and doesn't forward proceeds for donations that aren't clothing.

Savers Settlement. Savers entered into a settlement agreement. The highlights of the settlement were:

The following attachments give background to the proceeding:

The Savers compliance audit.

The Savers lawsuit.

Savers Motion for Temporary Restraining Order

The Savers settlement.