at 612-315-3037 or

www.swansonhatch.com

While the Great Recession didn’t create “Zombie Debt,” it elevated what was an obscure practice into a financial nightmare.

The large-scale sale and purchase of charged-off debt portfolios had its start in the aftermath of the savings and loan crisis. The 1980s had its own fiscal crisis in the banking industry, with both unemployment and inflation in the double digits. Interest rates on mortgages skyrocketed to 18%. The increase in rates was in large part due to inflation driven in part by the energy crisis. High interest rates drove down the price of real estate, whether it be homes or farms, because buyers could not afford to pay the principle and interest on an 18% mortgage. With the monthly payment so high, real estate values plunged, and lenders that relied on real-estate as collateral discovered that their loans were no longer fully secured. Many banks and a whole lot of savings & loans associations (S&Ls) collapsed, so much so that the federal government created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) to merge the failed banks and S&Ls into other institutions and then sell the assets (the loans) to private companies. This process continued through the early 1990s and was largely dormant in the late 1990s.

The Great Recession began with the failure of Wall Street Banks in 2008. Credit card companies, telephone companies, utilities, school lenders and banks ended up with large portfolios of debt that in previous years would have been written off the books. Now, with the advent of debt buyers, private companies went in and bought what otherwise was worthless debt for pennies on the dollar. The Federal Trade Commission estimated that credit card debt accounts made up 65% of the face-value of debts purchased from 2008 to 2012. Other types of debt purchased included cell phone bills, auto loan deficiencies, student loans, and mortgage deficiencies.

In 2014, the Debt Buyer’s Association reports that it had over 400 debt members, almost all of which were private companies. From 2006 through 2009, the top nine debt buyers purchased more than 500 portfolios comprising almost 90 million customer accounts and approximately $143 billion in consumer debt. These companies paid less than $6.5 billion for the debt. In 2008, nine debt buyers acquired more than 75% of the debt.

The debt buyers purchased a loan portfolio in the form of an electronic database or spreadsheet. They usually did not receive the loan file or even know the performance of the debtor. The spreadsheet generally had the debtor’s name, address, the amount allegedly owed, and the date and the amount of the last payment. The debt buyer received no documentation regarding the credibility of the loan.

In general, the debt buyer hired collectors and lawyers who badgered the debtor and eventually often sued them. Consumers faced harm from debt-buyer litigation abuses, such as (1) defective, inaccurate, and/or insufficient proof of debt; (2) robo-signing; (3) suing to collect “time-barred” debt; (4) “zombie debt”; and (5) “sewer” service. The debt buying industry was new to regulators, with little regulation to address these issues.

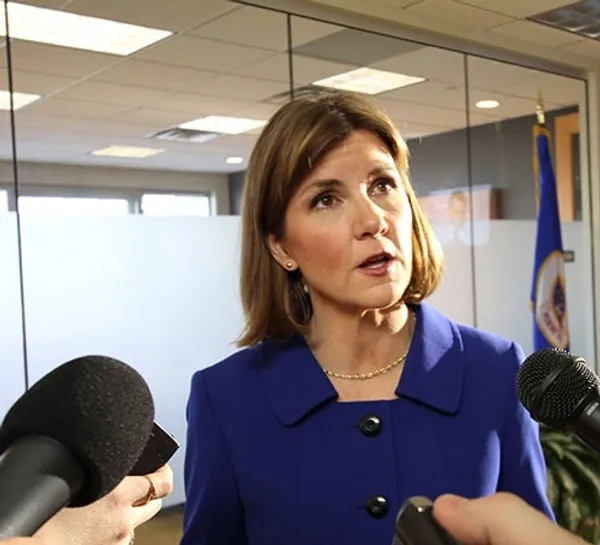

Lori Swanson filed the first attorney general enforcement action in the country against a “robosigner” in 2011. The defendant was Midland Funding, LLC. (“Midland”). Midland is one of the largest “debt buyers” in the country, a subsidiary of Encore Capital Group, a public company.

Midland filed more lawsuits in Minnesota than any other entity The StarTribunestated that Midland filed 15,000 cases in Minnesota from 2008 to 2011 and obtained over $30 million in judgments against Minnesota debtors in from 2005 through 2009, the most of any collection firm. According to the StarTribune, Midland filed 245,000 consumer lawsuits in 2009.

As noted above, the debt portfolio acquired by a debt buyer usually doesn’t contain written documents. It is electronic data that usually has only line for each debt: the name and address of the debtor, the date of last payment by the buyer, and the amount due. The buyer may have no idea as to product or service delivered for the debt, the identity of the debtor, the defenses claimed by the debtor, or when the debt was originally incurred. Indeed, the debt buyer usually never receives any of the underlying charge slips and contracts to prove money is owed.

This created a dilemma for Midland, because its primary collection tool is a lawsuit; to get a judgment, however, the company must file an affidavit with the court stating various facts concerning the basic allegation of the claim. The problem is that Midland didn’t have access to these basic facts. Midland found a solution. It arranged for its employees in St. Cloud Minnesota to “robo-sign” affidavits. Midland’s employees admitted signing up to 400 affidavits a day without reading them or verifying whether a debt was owed. Often, the debts were 10 or more years old, known as "zombie debt." Employees said that they had no way to determine the accuracy of the affidavits, allowing thousands of false and deceptive lawsuits to be filed across the country against consumers who don’t owe the money.

The Star Tribune article referenced a man from Brooklyn Park. He said he discovered he had been a victim of Midland's tactics a year ago, when his credit card company reduced his credit limit because of a "derogatory statement" in his credit report. It turned out that Midland had sued him five years earlier, obtained a judgment for $1,155 and was ready to garnish his paycheck or other assets.

But the man didn't owe anyone money, and the order to appear in court to prove his innocence was sent to an address where had hadn't lived for 23 years. He contacted Swanson, who then contacted the debt collector’s law firm. The law firm dropped the case.

Swanson identified three Midland employees who verified that they never read nor followed up to verify the affidavits they signed.

Swanson claimed that Midland’s conduct was tantamount to being a fraud on the court for filing false affidavits around the country. She also alleged that Midland violated the Fair Debt Collections Act because it misrepresented that people owed money they didn’t owe. She also alleged that Midland was unjustly enriched by its conduct.

The lawsuit was settled with a Consent Judgment in December of 2012. The Consent Judgment set forth strict requirements that needed to be met before a judgment could be entered.

First, Midland had to send a validation letter to a Minnesota resident before initiating a lawsuit, including the name of the creditor, the account number, the name of the owner of the account, the amount claimed to be owed, the date when the statute of limitations expired on the claim, the date when the claim is considered obsolete under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and all other information required by the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act.

Second, if Midland received an objection from the alleged debtor, it had to confirm the above information to the alleged debtor. In addition, Midland had to break down the amount of the claim that related to principal and the amount that related to interest and fees. Finally, it had to send a copy of the contract the debtor allegedly signed with the original creditor, as well as a copy of the underlying account statement that previously was sent by the original creditor. In addition, Midland had to prepare a statement as to whether the claim was time-barred under the applicable statute of limitations.

Third, in the normal court process, a formal “Answer” to Midland’s Complaint was required to be filed with the court by the alleged debtor. Midland had to adopt a new procedure where any “Answer” by the alleged debtor, even an oral statement, was sufficient to stop the process.

Fourth, robo-signing was prohibited. An affiant had to confirm every fact stated in an affidavit, which meant that the affiant had to inspect records which were not normally contained in the data sold to a debt buyer.

Midland was the first of a series of actions taken by Swanson in an effort to clean up the industry.

References:

Swanson v Midland Funding:

Complaint: Download below.

Consent Judgment: Download below.